Persepolis

Persepolis is the Greek name (from perses polis for 'Persian City') also known as Takht-e-Jamshid (Modern Persian: تخت جمشید, literally meaning "the throne of Jamshid"), for the ancient city of Parsa, located seventy miles northeast of Shiraz in present-day Iran. The name Parsa meant 'City of The Persians' and construction began at the site in 518 BCE under the rule of King Darius the Great ( who reigned 522-486 BCE). Darius made Parsa the new capital of the Persian Empire, instead of Pasargadae, the old capital and burial place of King Cyrus the Great. Because of its remote location in the mountains, however, travel to Parsa was almost impossible during the rainy season of the Persian winter when paths turned to mud and so the city was used mainly in the spring and summer warmer seasons. Administration of the Achaemenian Empire was overseen from Susa, from Babylon or from Ecbatana during the cold seasons and it was most likely for this reason that the Greeks never knew of Parsa until it was sacked and looted by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE (the historian Plutarch claiming that Alexander carried away the treasures of Parsa on the backs of 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels).

Though building began under Darius, the glory of Parsa which Alexander found when he invaded was due mainly to the latter works of Xerxes I and Artaxerxes III, both of whose names have been found (besides that of Darius) inscribed on tablets, over doorways and in hallways throughout the ruins of the city.

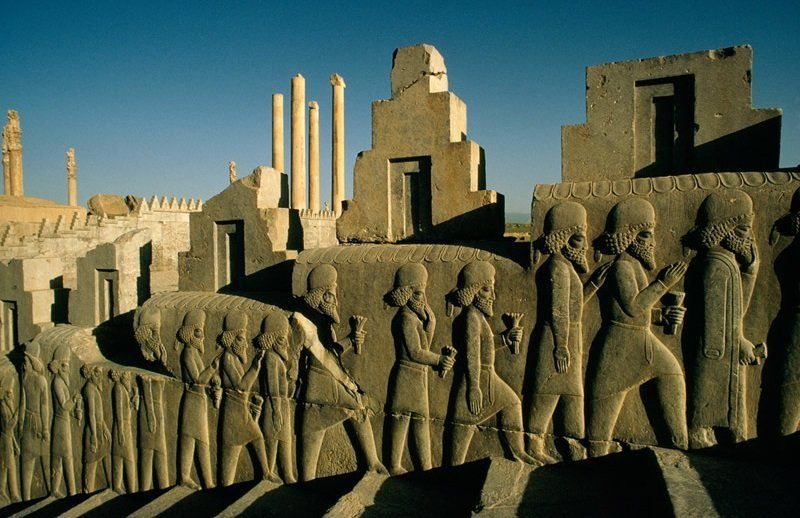

The great city of Persepolis was built in terraces up from the river Pulwar to rise on a larger terrace of over 125,000 square feet, partly cut out of the Mountain Kuh-e Rahmet ("the Mountain of Mercy"). To create the level terrace, large depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks which were then fastened together with metal clips; upon this ground the first palace at Persepolis slowly grew. Around 515 BCE, construction of a broad stairway was begun up to the palace doors. This grand, dual entrance to the palace, known as the Persepolitan stairway, was a masterpiece of symmetry on the western side of the building and the steps were so wide that Persian royalty and those of noble birth could ascend or descend the stairs by horseback, thereby not having to touch the ground with their feet. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of all Nations.

The great palace built by Xerxes I consisted of a grand hall that was eighty-two feet in length, with four large columns, the entrance on the Western Wall. Here the nations which were subject to the Empire gave their tribute to the king. There were two doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other opening onto a winding road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal. Off the Apadana yard, near the Gates of all Nations, was Darius’ great Apadana Hall, where he would receive dignitaries and guests which, by all accounts, was a place of stunning beauty (thirteen of the pillars of the Hall still stand today and remain very impressive).

Limestone was the main building material used in Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated cistern was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain to catch rain water for drinking and bathing.

The terraced plan of the site around the palace walls enabled the Persians to easily defend any section of the front. The ancient historian Diodorus Siculus recorded that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, all with fortified towers, always manned. The first wall was over seven feet tall, the second, fourteen feet, and the third wall, surrounding all four sides, was thirty feet high. With such fortifications opposing him it is an impressive feat that Alexander the Great managed to overthrow such a city; but overthrow it he did. Diodorus provides the story of the destruction of Persepolis:

“Alexander held games in honor of his victories. He performed costly sacrifices to the gods and entertained his friends bountifully. While they were feasting and the drinking was far advanced, as they began to be drunken, a madness took possession of the minds of the intoxicated guests. At this point one of the women present, Thais by name and Athenian by origin, said that for Alexander it would be the finest of all his feats in Asia if he joined them in a triumphal procession, set fire to the palaces, and permitted women's hands in a minute to extinguish the famed accomplishments of the Persians. This was said to men who were still young and giddy with wine, and so, as would be expected, someone shouted out to form up and to light torches, and urged all to take vengeance for the destruction of the Greek temples [burned by the Persians when they invaded Athens in 480 BCE]. Others took up the cry and said that this was a deed worthy of Alexander alone. When the king had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honor of the god Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thais the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was most remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport.”

The fire, which consumed Persepolis so completely that only the columns, stairways and doorways remained of the great palace, also destroyed the great religious works of the Persians written on “prepared cow-skins in gold ink” as well as their works of art. The palace of Xerxes, who had planned and executed the invasion of Greece in 480, received especially brutal treatment in the destruction of the complex. The city lay crushed under the weight of its own ruin (although, for a time, nominally still the capital of the now-defeated Empire) and was lost to time. It became known to residents of the area only as 'the place of the forty columns’(for the still-remaining columns standing among the wreckage) until, in 1618 CE, the site was identified as Persepolis. In 1931 excavations were begun which revealed the glory which had once been Persepolis.

The exact date of the founding of Persepolis is not known. It is assumed that Darius I began work on the platform and its structures between 518 and 516 B.C., visualizing Persepolis as a show place and the seat of his vast Achaemenian Empire. He proudly proclaimed his achievement; there is an excavated foundation inscription that reads, “And Ahuramazda was of such a mind, together with all the other gods, that this fortress (should) be built. And (so) I built it. And I built it secure and beautiful and adequate, just as I was intending to.” But the security and splendor of Persepolis lasted only two centuries. Its majestic audience halls and residential palaces perished in flames when Alexander the Great conquered and looted Persepolis in 330 B.C. and, according to Plutarch, carried away its treasures on 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels.

From the time of its barbaric destruction until A.D. 1620, when its site was first identified, Persepolis lay buried under its own ruins. During the following centuries many people traveled to and described Persepolis and the ruins of its Achaemenid palaces. Many of their observations were later condensed and published by George N. Curzon in Persia and the Persian Question (London and New York, 1892). But scholarly and scientifically planned work was not undertaken until 1931. Then Ernst Herzfeld, at that time Professor of Oriental Archaeology in Berlin, was commissioned by James H. Breasted, Director of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, to undertake a thorough exploration, excavation and, if possible, restoration of the remains of Persepolis. Thus, Herzfeld, in 1931 became the first field director of the Oriental Institute’s Persepolis Expeditions. In 1931–34, assisted by his architect, Fritz Krefter, he uncovered on the Persepolis Terrace the beautiful Eastern Stairway of the Apadana and the small stairs of the Council Hall. He also excavated the Harem of Xerxes. When Herzfeld left in 1934, Erich F. Schmidt took charge. He continued the large-scale excavations of the Persepolis complex and its environs until the end of 1939, when the onset of the war in Europe put an end to his archaeological work in Iran. During the last years of excavating, the University Museum in Philadelphia and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had joined the Oriental Institute in order to cope with the tremendous work at hand.

Schmidt’s expedition staff, though varying from year to year, consisted mainly of his assistant Donald E. McCown, architect John S. Bolles and assistant Elliot F. Noyes (both later replaced in 1937 by Richard C. Haines), photographer Boris Dubensky, and various draftsmen, recorders, mechanics, and the like. The digging crew, recruited from villagers, fluctuated from 200 to 500 men. Elaborating on this, Schmidt wrote that at the beginning of each season about 20 to 30 laborers arrived from Damghan, old-time workers, honest peasants and trusted hands, who were trained for the delicate job of excavating. They, in turn, recruited the bulk of the digging crew.

Persepolis Terrace: Architecture, Reliefs, And Finds

The magnificent palace complex at Persepolis was founded by Darius the Great around 518 B.C., although more than a century passed before it was finally completed. Conceived to be the seat of government for the Achaemenian kings and a center for receptions and ceremonial festivities, the wealth of the Persian empire was evident in all aspects of its construction. The splendor of Persepolis, however, was short-lived; the palaces were looted and burned by Alexander the Great in 331–330 B.C. The ruins were not excavated until the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago sponsored an archaeological expedition to Persepolis and its environs under the supervision of Professor Ernst Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934, and Erich F. Schmidt from 1934 to 1939.

- Palace Complex: Structures, Reliefs, and Inscriptions

- The Apadana

- The Throne Hall

- The Gate of All Nations

- The Treasury

- The Palace of Darius

- The Palace of Xerxes

- The Council Hall

- The Harem of Xerxes

- Miscellaneous Structures at Persepolis

- Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries

- Cuneiform Tablets

- Seals and Seal Impressions

- Miscellaneous Finds

- Sculpture

- The Royal Tombs and Other Monuments

- The Sasanian Rock Reliefs at Naqsh-i-Rustam and Naqsh-i-Rajab

- The Ka’bah-i-Zardusht

The magnificent ruins of Persepolis lie at the foot of Kuh-i-Rahmat, or “Mountain of Mercy,” in the plain of Marv Dasht about 400 miles south of the present capital city of Teheran.

The exact date of the founding of Persepolis is not known. It is assumed that Darius I began work on the platform and its structures between 518 and 516 B.C., visualizing Persepolis as a show place and the seat of his vast Achaemenian Empire. He proudly proclaimed his achievement; there is an excavated foundation inscription that reads, “And Ahuramazda was of such a mind, together with all the other gods, that this fortress (should) be built. And (so) I built it. And I built it secure and beautiful and adequate, just as I was intending to.” But the security and splendor of Persepolis lasted only two centuries. Its majestic audience halls and residential palaces perished in flames when Alexander the Great conquered and looted Persepolis in 330 B.C. and, according to Plutarch, carried away its treasures on 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels.

From the time of its barbaric destruction until A.D. 1620, when its site was first identified, Persepolis lay buried under its own ruins. During the following centuries many people traveled to and described Persepolis and the ruins of its Achaemenid palaces. Many of their observations were later condensed and published by George N. Curzon in Persia and the Persian Question (London and New York, 1892). But scholarly and scientifically planned work was not undertaken until 1931. Then Ernst Herzfeld, at that time Professor of Oriental Archaeology in Berlin, was commissioned by James H. Breasted, Director of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, to undertake a thorough exploration, excavation and, if possible, restoration of the remains of Persepolis. Thus, Herzfeld, in 1931 became the first field director of the Oriental Institute’s Persepolis Expeditions. In 1931–34, assisted by his architect, Fritz Krefter, he uncovered on the Persepolis Terrace the beautiful Eastern Stairway of the Apadana and the small stairs of the Council Hall. He also excavated the Harem of Xerxes. When Herzfeld left in 1934, Erich F. Schmidt took charge. He continued the large-scale excavations of the Persepolis complex and its environs until the end of 1939, when the onset of the war in Europe put an end to his archaeological work in Iran. During the last years of excavating, the University Museum in Philadelphia and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had joined the Oriental Institute in order to cope with the tremendous work at hand.

Schmidt’s expedition staff, though varying from year to year, consisted mainly of his assistant Donald E. McCown, architect John S. Bolles and assistant Elliot F. Noyes (both later replaced in 1937 by Richard C. Haines), photographer Boris Dubensky, and various draftsmen, recorders, mechanics, and the like. The digging crew, recruited from villagers, fluctuated from 200 to 500 men. Elaborating on this, Schmidt wrote that at the beginning of each season about 20 to 30 laborers arrived from Damghan, old-time workers, honest peasants and trusted hands, who were trained for the delicate job of excavating. They, in turn, recruited the bulk of the digging crew.

Palace Complex: Structures, Reliefs, and Inscriptions

This section deals mainly with the architecture of the palace complex, and its buildings and embellishing reliefs. These date entirely from the Achaemenian period (518–331/30 B.C.) except for a few remnants of post-Achaemenid structures.

An inscription carved on the southern face of the Terrace proves that Darius the Great was the founder of Persepolis. Work was started about 518 B.C., although the tremendous task was not completed until about 100 years later by Artaxerxes I. Before any of the buildings could be erected, considerable work had to be done. This mainly involved cutting into an irregular and rocky mountainside in order to shape and raise the large platform and to fill the gaps and depressions with rubble.

According to tablets inscribed in Old Persian and Elamite found at Persepolis, it seems that Darius planned this impressive complex of palaces not only as the seat of government but also, and primarily, as a show place and a spectacular center for the receptions and festivals of the Achaemenian kings and their empire. Darius lived long enough to see only a small part of his plans executed. His brilliant and grandiose ideas were taken up and followed by his son and successor Xerxes, who, according to an excavated foundation inscription, said: “When my father Darius went (away from) the throne, I by the grace of Ahuramazda became king on my father’s throne. After I became king…what had been done by my father, that I also (did), and other works I added.”4 Actually, the Persepolis we know is mostly the work of Xerxes.

In dealing with the Persepolis platform, we have to understand that the northern part of the Terrace, consisting mainly of the Audience Hall of the Apadana, the Throne Hall, and the Gate of Xerxes, represented the official section of the Persepolis complex, accessible to a restricted public. The other part held the Palaces of Darius and Xerxes, the Harem, the Council Hall, and such. Following is a brief enumeration of the buildings, and their most outstanding features, that constitute the Terrace complex.

The Apadana

Darius the Great built the greatest palace at Persepolis on the western side. This palace was called the Apadana. The King of Kings used it for official audiences. The work began in 515 BC, and his son, Xerxes I, completed it 30 years later. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60 meters (200 ft) long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Each column is 19 meters (62 ft) high with a square Taurus (bull) and plinth. The columns carried the weight of the vast and heavy ceiling. The tops of the columns were made from animal sculptures such as two-headed bulls, lions and eagles. The columns were joined to each other with the help of oak and cedar beams, which were brought from Lebanon. The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco to a depth of 5 cm, which was used for bonding, and then covered with the greenish stucco which is found throughout the palaces.

At the western, northern and eastern sides of the palace, there were three rectangular porticos each of which had twelve columns in two rows of six. At the south of the grand hall, a series of rooms were built for storage. Two grand Persepolitan stairways were built, symmetrical to each other and connected to the stone foundations. To protect the roof from erosion, vertical drains were built through the brick walls. In the four corners of Apadana, facing outwards, four towers were built.

The walls were tiled and decorated with pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers. Darius ordered his name and the details of his empire to be written in gold and silver on plates, which were placed in covered stone boxes in the foundations under the Four Corners of the palace. Two Persepolitan style symmetrical stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of Apadana to compensate for a difference in level. Two other stairways stood in the middle of the building. The external front views of the palace were embossed with carvings of the Immortals, the Kings' elite guards. The northern stairway was completed during the reign of Darius I, but the other stairway was completed much later.

The Throne Hall

Next to the Apadana, the second largest building of the Persepolis Terrace is the Throne Hall (also called the “Hundred-Column Hall”), which was started by Xerxes and completed by his son Artaxerxes I (end of the fifth century B.C.). Its eight stone doorways are decorated on the south and north with reliefs of throne scenes and on the east and west with scenes depicting the king in combat with monsters. In addition, the northern portico of the building is flanked by two colossal stone bulls. In the beginning of Xerxes’ reign the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for representatives of all the subject nations of the empire. Later, when the Treasury proved to be too small, the Throne Hall also served as a storehouse and, above all, as a place to display more adequately objects, both tribute and booty, from the royal treasury. Concerning this, Schmidt wrote of the striking parallel in a modern example of a combined throne hall and palace museum where the Shah of Iran stores and exhibits the royal treasures in rooms and galleries adjoining his throne hall in the Gulistan Palace at Tehran.

The Gate of All Nations

To the north of the Apadana stands the impressive Gate of Xerxes, from which a broad stairway descends. Xerxes, who built this structure, named it “The Gate of All Nations ,” for all visitors had to pass through this, the only entrance to the terrace, on their way to the Throne Hall to pay homage to the king. The building consisted of one spacious room whose roof was supported by four stone columns with bell-shaped bases. Parallel to the inner walls of this room ran a stone bench, interrupted at the doorways. The exterior walls of the structure, made of thick mud brick, were decorated with numerous niches. Each of the three walls, on the east, west, and south, had a very large stone doorway. A pair of colossal bulls guarded the western entrance; two assyrianized man-bulls stood at the eastern doorway. Engraved above each of the four colossi is a trilingual inscription attesting to Xerxes having built and completed the gate. The doorway on the south, opening toward the Apadana, is the widest of the three. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they must have had two-leaved doors, which were probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornamented metal.

The Treasury

Adjacent to the Throne Hall is the Treasury, part of which served as an armory and especially as a royal storehouse of the Achaemenian kings. The tremendous wealth stored here came from the booty of conquered nations and from the annual tribute sent by the peoples of the empire to the king on the occasion of the New Year’s feast. Before the Throne Hall was finished, the most spacious room of the Treasury was used as a Court of Reception. Two large stone reliefs were discovered here that attested to its function. These depict Darius I, seated on his throne, being approached by a high dignitary whose hand is raised to his mouth in a gesture of respectful greeting. Behind the king stands Crown Prince Xerxes, followed by court officials.

The Palace of Darius

Twelve columns supported the roof of the central hall from which three small stairways descend. Reliefs on these stairways depict servants coming up the steps carrying animals and food in covered dishes to be served at the king’s tables. On the eastern and western doorjambs are reliefs showing the king in formal dress leaving the palace, followed by two attendants; reliefs on the northern and southern doorways depict the king in combat with monsters.

The Palace of Xerxes

Xerxes’ Palace, almost twice as large as that of Darius, shows very similar decorative features on its stone doorframes and windows, except for two large Xerxes inscriptions on the eastern and western doorways. Instead of showing the king’s combat with monsters, these doorways depict servants with ibexes. Unfortunately, all the reliefs in this palace are far less well preserved than those of the Palace of Darius.

The Council Hall

Access to the royal apartments was by means of a beautiful stairway which led to three entrances. Two were for official purposes; the third was a secret doorway which led into the Harem.

The Harem of Xerxes

The Harem, where the royal ladies lived, was constructed in an L-shaped form. The main wing was oriented north-south; the west wing extended westward from the southern portion of the main wing.

The nucleus of the main wing was a large centrally placed columned hall with a portico facing a spacious courtyard on the north. The hall had four doorways whose jambs were decorated with reliefs. On the jambs of the southern doorway Xerxes is depicted entering the hall. He is followed by two attendants; one is carrying a fly whisk and the other is holding a parasol over the king’s head. On the jamb of the eastern doorway there is a relief showing Xerxes fighting a lion-headed monster. The reliefs on the western doorway show the king in combat with a lion. The queen’s quarters are not definitely known, but this impressive central section was probably reserved for her and her retinue.

South of the columned hall, the main wing contained six apartments arranged in two rows. Each apartment consisted of a large pillared room and one or sometimes two smaller rooms. The west wing contained sixteen additional apartments, similarly laid out.

In addition to the access from the Council Hall to the northern part of the main wing of the Harem, two stairways connected the west wing with the Palace of Xerxes. There were also two exits to courtyards or enclosed gardens. A third exit at the eastern end of the western wing may have led to an open area or perhaps to an enclosed area whose limits have been destroyed.

The main wing of the Harem was excavated and restored by Herzfeld. A large part of the building, besides serving as living quarters for the expedition staff, was converted into workrooms, where the cleaning, labeling, and restoring of objects were undertaken. Finally, the front of the Harem was restored and made into a museum to display some of the objects found at Persepolis.

Miscellaneous Structures at Persepolis

Near the southeast corner of the Terrace, at the foot of the mountain, were buildings of modest size and insubstantial structure, whose contents indicate that they were quarters for members of the garrison and perhaps for artisans (red). Immediately to the east was a square mudbrick tower, one of a row of towers linked by a 10-meter thick wall that ran along the east edge of the terrace at the foot of the Kuh-i Rahmat and joined the towered defensive wall that ran from the corners of the Terrace up the slope and along the crest of the Kuh-i Rahmat.

The southwestern corner of the Terrace, west of the palace of Xerxes, may once have been the site of a palace of Artaxerxes I, but the standing remains found there belonged a residential structure called Palace H (green), cobbled together by an unknown post-Achaemenid builder from reused pieces of building material and ornament brought from older structures on the Terrace. The standing remains of Palace G (cyan), north of the Palace of Xerxes, were also from a post-Achaemenid construction on the site of a destroyed older building, perhaps a palace of Artaxerxes III. To the east of the Palace of Xerxes were scraps of Palace D (yellow), probably the substructure of another building that incorporated debris from Achaemenid buildings. Other post-Achaemenid remains included burials in clay coffins were near the spring about 1 km north of the terrace, in a recess at the foot of the mountain.

Panorama of Persepolis

Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries

What early historians wrote about the wealth of Persepolis certainly was not exaggerated. Thus we learn from the reports of the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus that Persepolis was the wealthiest city under the sun and her houses were full of gold and silver and all sorts of riches. On the basis of his and others’ accounts, one would have expected the Oriental Institute’s expeditions to find an enormous yield of objects. Unfortunately, Alexander and his army did a very thorough job of looting and burning Persepolis in 331/30 B.C. What the Oriental Institute recovered were objects either overlooked or dropped accidentally by the Macedonians.

By far the largest number of finds were from the royal storehouse in the Treasury. Additional objects-far fewer-came from other buildings of the Terrace. Many of these finds were pieces of booty from wars with foreign nations, such as Greece, Egypt, and India, or tokens of tribute from the subject nations of the empire. Some native objects clearly show foreign cultural influences. We know from excavated tablets that Darius I had called to his court many foreign artists and workers whose skill and inspiration were utilized, but never copied, by the Persians.

Cuneiform Tablets

Uncovered in the debris of the Treasury were hundreds of clay tablets with inscriptions in Elamite cuneiform. These tablets, originally sundried, were baked in the heat of the immense fire that destroyed the building, so that many were found intact instead of having crumbled to dust long ago. These tablets, written for the most part in Old Persian and its corresponding translations of Elamite and Babylonian, were of great value to the excavators. We learn from them of the presence in Persepolis of skilled workmen from many parts of the empire, of stone-relief and inscription workers from Egypt, goldsmiths from Caria, and ornament makers from Susa. Some tablets also mention the month and year of the reign of either Darius or Xerxes when a particular work was executed and the amount of compensation-either in kind or in money-the workers received. Other tablets bear records of sales, of land deals, of taxes to be paid, or of the amount of money borrowed from the treasury. Finally, some tablets give instructions about how much haoma, the sacred intoxicating drink, could or should be used at a cult service.

Seals and Seal Impressions

The chronology of the Persepolis finds was traceable largely through the inscriptions on seals, wall pegs, and foundation slabs, that were discovered. Each usually bore the name of the Achaemenid ruler of its time. Cylinder seals, generally made of stone, often depict, among other subjects, martial or hunting scenes, rituals and offerings, or fights between animals. The royal seals of Darius and Xerxes always depict a king victorious in his fight with ferocious animals or monsters, a scene also depicted in the royal reliefs.

Miscellaneous Finds

Fragments of vessels, whose inscriptions indicate that they were used at the king’s table, were also found in the debris. Other finds were ritual objects, mortars and pestels, weights, and tools. Finally, hundreds of pieces of martial equipment were found in the Treasury and in the garrison quarters, e. g., arrowheads, scabbard tips, and bridle ornaments.

Since Alexander’s men were so thorough in destroying and looting Persepolis, only a few pieces of jewelry, several gold and silver coins, and some silver buttons were found; not one vessel of precious metal was recovered. However, several alabaster bowls and bottles were excavated, some with inscriptions and dates that prove them to be tribute sent to Persepolis from Egypt during the reigns of Darius and Xerxes. Other vessels were made of a bluish-green artificial compound of copper-calcium-tetrasilicate known as “Egyptian blue.” These were a much-valued import from Egypt, where the secret of manufacturing this paste had been known since the Fourth Dynasty.

Sculpture

As far as is known, there were few freestanding monumental statues at Persepolis. Sculpture in the round was mainly used in connection with or attached to architecture-for instance, the guardian bulls of the Throne Hall, the double-headed bull capital, or the entrance sculptures of mastiffs. A few small sculptures were found, however; a unique bronze pedestal of three lions from the Treasury, probably used to support the legs of a throne, and a few small bronze figurines and a baked clay head of a Persian. In addition, there were also sculptural ornamentations — winged griffins, swans, and lions applied to metal vases and stone trays.

The Royal Tombs and Other Monuments

It is commonly accepted that Cyrus the Great was buried in Pasargadae, which is mentioned by Ctesias as his own city. If it is true that the body of Cambyses II was brought home "to the Persians," his burying place must be somewhere beside that of his father. Ctesias assumes that it was the custom for a king to prepare his own tomb during his lifetime. About 4.8 kilometers northwest of Persepolis lies the imposing site of Naqsh-i-Rustam in the mountain range of Husain Kuh, where Darius the Great and his successors had their monumental tombs carved into the cliff. Here in 1933 Herzfeld conducted a short survey and made soundings, but it was not until 1936 that Schmidt started to clear and document the royal tombs and to excavate the Ka'bah-i-Zardusht.

Although Naqsh-i-Rustam had long been a sacred area (as the remains of a Pre-Achaemenid relief show), Darius the Great was the first to choose it as a burial place. His successors not only imitated his idea of a cliff tomb but also copied the layout of the tomb itself. The dramatic facade of the tomb is constructed like a cross. An entrance leads into the tomb chamber, cut deep into the rock. In the panel above this facade is a relief depicting the king standing on a three-stepped pedestal in front of an altar. His hand is raised in a gesture of worship. Above him floats the winged disk of Ahuramazda, god of the Zoroastrian religion. This scene is supported by throne bearers representing the twenty-eight nations of the empire. On the side panels are the king's weapon bearers and the Persian guards. The trilingual cuneiform inscriptions on three panels of the rock wall either enumerate the twenty-eight nations upholding the throne or glorify the king and his rule. Some traces of pigment found on the facade of the royal tombs suggest that all or most of the stone reliefs had been painted.

Only the tomb of Darius I can be identified beyond doubt by inscriptions. The three other tombs at Naqsh-i Rustam are attributed to his immediate successors, Xerxes, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. Other royal tombs of similar form, thought to be those of the later Achaemenids, were built at Persepolis itself, cut into the rock face of the Kuh-i Rahmat, overlooking the Terrace. The two complete tombs are assigned to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III; an incomplete tomb was perhaps meant for the last Achaemenid king, Darius III. About 2 km south of Naqsh-i Rustam, on the south bank of the river Pulvar, are the remains of an unfinished freestanding structure, perhaps the base of a tomb intended for Cambyses II, modeled on the imposing tomb of his father, Cyrus the Great, at Pasargadae, up the Pulvar 43 km northeast of Persepolis.

The Sasanian Rock Reliefs at Naqsh-i-Rustam and Naqsh-i-Rajab

The rock reliefs at Naqsh-i-Rustam and Naqsh-i-Rajab, quite impressive and well-known works of art, date from the third century A.D. There are two groups of these reliefs in the Persepolis area. Nine reliefs are hewn into the rock below the royal tombs at Naqsh-i-Rustam; each relief is set in a rectangular recess. There is another group of four reliefs at Naqsh-i-Rajab, about three kilometers north of Persepolis. These reliefs are carved into three sides of a grottolike bay at the foot of the Mountain of Mercy. The exact purpose of this recess is not known, but it seems to have been a place of religious significance even before the Sasanian kings came to power. Since interpretations of the rock reliefs, both at Naqsh-i-Rustam and Naqsh-i-Rajab, are still varied and disputed, and since only a few of these reliefs have inscriptions, their identification-that is, dating-has had to be based mainly on depictions of specific kings on coins of the Sasanian period. Thus it seems that the earliest of these reliefs is one at Naqsh-i-Rajab. It shows an investiture scene of Ardashir I, founder of the Sasanian Empire (226–40 A.D.) by the god Hormizd (Ahuramazda), who is represented here in human shape. God and king are both standing and are of equal height. Only the fact that the god holds the diadem and the king reaches for it shows the dependence of the mortal king on the favors of the highest god. What makes this relief historically so important is its inscription by the priest Kartir, who was not only the founder of the Sasanian state church but also played an important role in politics. This inscription, proclaiming his personal beliefs, shows Kartir with hand raised in a gesture of homage to the god and the king. Another relief at Naqsh-i-Rajab depicts the investiture of Shapur I (241–72 A.D.), son and successor of Ardashir I. In an adjoining relief Shapur I is shown on horseback, followed by nine court attendants on foot.

Of the nine reliefs carved into the rock below the royal tombs at Naqsh-i-Rustam, the most important depicts the victory of Shapur I over the Roman emperor Valerian, whom he defeated and captured at Edessa in 260 A.D. The relief shows the king seated on his horse and Valerian kneeling in front of him. To the right of this scene is another inscription by Kartir, attesting to the victory and triumph of the Persian king over the Roman army—an unparalleled event in the reign of Shapur I. The rest of the Naqsh-i-Rustam rock reliefs deal mainly with equestrian scenes, showing various kings, e. g., Bahram II and Hormizd II.

The Ka’bah-i-Zardusht

Facing the cliffs of Naqsh-i-Rustam and their royal tombs stands the Ka'bah-i-Zardusht, which was probably built in the first half of the sixth century B.C. This square tower, forty-one feet high and twenty-four feet square, rises from a terraced platform. It is constructed of large blocks of limestone joined without mortar and held together by means of iron cramps. Stone steps lead up to the entrance, which opens into a large single room. Scholarly opinions about the purpose of the Ka'bah are divided. Some think that it was the burial place of an early Achaemenian king; others, that it was later used as a fire temple of the goddess Anahita, where the Sasanian kings were crowned.

In 1936 excavations of the tower uncovered a Sasanian trilingual inscription, in Middle Persian, Greek, and Parthian, that Shapur I had had engraved on three sides of the structure. In it he described his three victorious campaigns against Rome (between 243 and 260 A.D.). Scholars today accept this description as historical fact. It is also an important record, for this was the last time that Greek was used in Iranian inscriptions.

Panorama of Persepolis

Further Reading: